Stories Of How My Pets Communicate

We have all seen videos of pets making a noise that sounds like human speech. Dogs howling “I love you”, cats yowling “Hello”, and of course we all expect birds to pick up some vocabulary when they are around us. Do these animals really know what they are doing? Most don’t, of course, but there are some animals that do communicate in ways we consider to be language, like the gorillas that have learned to sign. So unless you have a gorilla, you’re out of luck when it comes to communicating with your pet, right? Not if you learn to talk the way your pet talks.

Animals have a language that is all their own and each species often has a different kind of language from the others. Just like humans, some are capable of learning how to “talk” in other languages, which is usually when you see those mixed species animal friend videos go viral on YouTube. How does that dog seem so happy with that deer? They have found that common ground in language between their species. I watch the videos and though my eye is untrained, I have no problems picking up some ideas rather quickly. Among other observations, the most obvious is that the deer has learned some of the dog’s playful body language and the dog has learned some of the deer’s neck grooming behaviours. There is just enough common ground between them to maintain that friendship, partly because they have learned to “talk” in the other’s language.

It is possible for humans to do the same thing, if we allow ourselves the time to learn. Animals will quite happily study our behaviours, mostly out of genetic necessity. Take our local deer; they freeze in place and stare at whatever strange thing is moving around them to try and decide if they should dash away for their lives. This is their nature. It is what keeps them alive. If the deer in your neighbourhood don’t do this, they have probably become too used to the human activities around them, which can be a dangerous situation with any wild animals.

We are lucky enough to live out beyond the rural boundary, where the deer haven’t adjusted to life with humans in a way that is unnatural for them. Still, loving animal communication since I was a child, I wanted a way to let them go about their lives while we went about ours without disturbing them too much, the way they would coexist with a bird or a squirrel. I didn’t want to open my door and walk to my car, terrifying an entire herd of deer in the process, so I began whistling when I saw them. It wasn’t a tune or anything, just a note once or twice, occasionally making sound. In this way I would move about my yard, not really looking at them or paying them too much attention at all. At first this confused them, but after some time they began to appreciate it. They are still wild animals, they remain unsure about my intentions and they do move deeper into the woods when they see me, but they aren’t dashing out into the country roads in a panic, to be hit by an unsuspecting driver who is coming around the bend at 45 miles an hour. They have learned that my typical behaviour is to exist in the yard, occasionally making a whistle sound and that this particular behaviour doesn’t harm them. They hear me and will casually wander into the woods, flicking their tails a little in agitation that I have disturbed their peace. The same trick also lets them know I am coming down the private drive we share with other families. A short whistle out the window lets them know I see them and I move forward while they shuffle into the trees. Most astonishingly, in recent years, the older deer have actually come to expect that we should announce ourselves to each other. If I do not see them, they will snort at me to let me know they are there, then flick their tails straight up and trot off into the woods, alerting that they aren’t comfortable with this unusually quiet behaviour on my part. This actually startles some guests at night, so be aware if you come visiting.

The deer aren’t my pets, and I wouldn’t ever want them to be, but I use them to prove the point that all animals have the capability to learn the behaviours of others, even the human variety. If we think about it, this should be obvious. When we see a bird in our yard, don’t we expect it to eventually fly off? Don’t we all know that a fish out of water is going to flop around in a desperate struggle to get back in? We know these things because we experience them in some way, either in life or on video. Well, our pets experience us regularly too. They have seen us get food from containers, they expect that we will sleep in the big rectangular fluffy thing instead of on the floor, and they know that we all love looking at that noisy light box on the wall or tapping our fingers on the smaller light boxes that we hold in our hands. If we are doing these things regularly, that must be the way of life. So when my rats, for example, hear me shuffle boxes around or move a plastic bag, they instantly expect that food is being handled, even if the plastic bag is being put in a pocket to use for the dog’s walk.

How do we increase our communication with our pets?

Some animals can be trained to respond to commands. Dogs are trained to sit, stay, beg, and do any other number of nifty things. They hear a word, they learn the behaviour that is expected at the mention of that word, then they do the thing required. It’s that simple. Sometimes you can go beyond that training and teach them to express themselves with the word they have learned. For example, one of our dogs, Sahara, loves belly rubs. She flops over, holds her short little leg up in the air and waits. You rub, then stop, and she turns to look at you as if to say, “Well? Where’s the rest?” I went a little farther with this expression, knowing that she was trying to ask for more. I taught her that if she touched her cheek when someone had given her a belly rub, she would get more belly rubs. It was an extension of the paw waving behaviour she was already displaying, so she picked it up quickly. When she realized I only rubbed her belly when she touched her cheek, and not when she put her paw in the air and looked at me, she transitioned to asking for “more” on a regular basis. Recently she has tried this once or twice when getting treats or dinner, all on her own, without prompting. We have created a monster.

I have also learned to “talk” with my cat, Sekhemkare, and some of my fish. With cats, of course, there are usually no issues at all in communication, since they either leave humans alone entirely or have no problem what so ever in telling us what to do. In the case of our cat, the story comes from replacing his favourite toy, “Piggy”, which had become filthy. We got him a new one and picked up the old one to throw away, only to discover in the morning that the old Piggy was happily resting in the middle of the living room floor while the new Piggy was drowned in the cat’s water dish. That message was clear; death to all imposters.

With my fish, communication has been an interesting ride. The best results came from Nix, Hydra, Pluto, and LaForge, who all learned how to get my attention by spitting into the corner of their tank. They quickly discovered that this sound would instigate my making sounds (talking to them) and moving closer to where they were. Each of them began to use this technique to “call” me the way you would call a dog or cat. LaForge was an only fish and Pluto was also alone for a time, and they were often perfectly content to have me walk over to the tank and sit beside them for a while. In their case this was a way of saying they wanted that “schooling” feeling of having another living thing there with them. Nix and Hydra are my current fish and use this “call” to tell me that I have forgotten to feed them at exactly the time that they expect to be fed. If I ignore the “call” they will often leap slightly from the water and knock into the lid of the tank, which I have decided must be their version of swearing at me for not hurrying up about it.

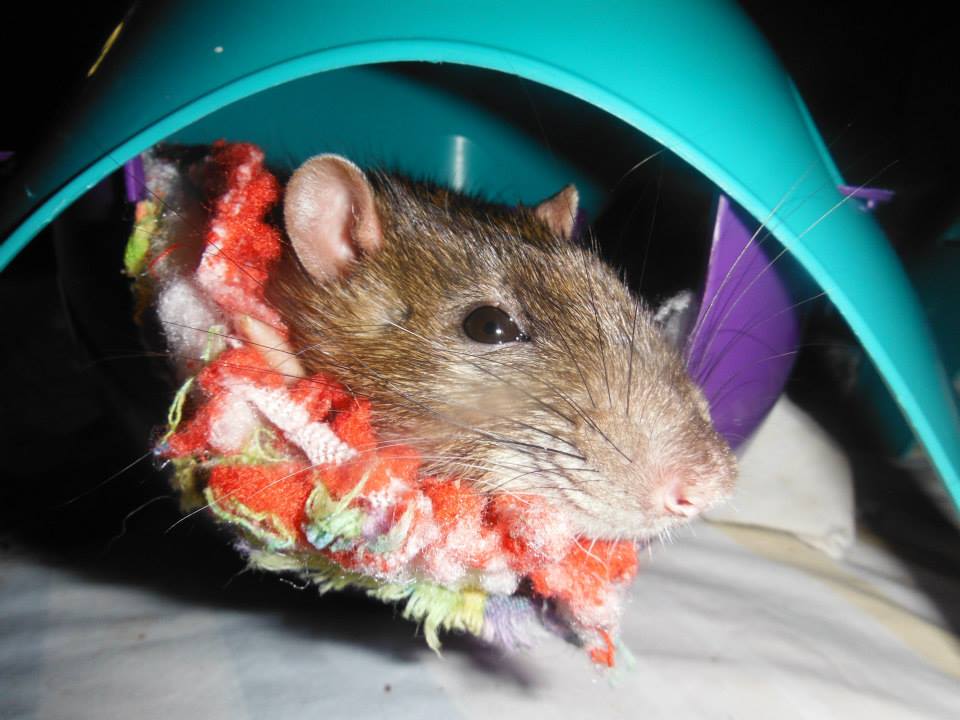

How My Pets Communicate: The Rats

Now we come back to the rats, who are probably the best communicators of any of the pets that I have. Their minds work more like human minds than just about any animal I have ever encountered. This is one of the reasons rats are so often studied in order to help humans. There are so many stories when it comes to rats talking with us that it is hard to pick one or two to share. We have had rats tap our cheeks or pull on our clothes to tell us where they want us to take them, we have had rats who have dictated exactly where they expect us to leave their food by dragging their dish to the proper place until we finally got the idea, we have a rat who learned to let himself out of his cage, but would only chew a tiny notch in the furniture, then go back inside and wait for us to notice. “See? I let myself out again. That’s three times this week, in case you are counting, like I am.”

Two of our rats have been such good communicators that I gave serious thought to teaching them to use technology to actually speak. Archie was the first of these and sadly he passed away at a very young age, before his training went very far. I learned of his abilities when I realized that he would actually listen to individual words and seemed to work out their meaning within a week or so. I would talk to him and when there was a word he was unfamiliar with, he would tilt his head and look very intent. He would do this repeatedly until he had learned the word. What do I mean by this? Take the word “water” for example. To sum up his vocabulary skills quickly, I will shorten his learning process to a few sentences, but it went something along these lines… I would be talking to him and say something like, “I’m going to get your water, be right back.” He would tilt his head and shift his ears forward, a clear sign he was listening to me. I would repeat the word I thought he was trying to learn: “Water?” If he repeated the head tilt, I knew this was the thing he was focused on, so I would then go and get the water bottle, put it in his cage and repeat the word “water”, usually in a sentence, sometimes on its own. After about a week, if he heard the word water, he would go to either his bottle or the sink, even if we weren’t talking to him. After some time of this, he began to tell us when he wanted fresh water by bonking his head under the bottle if we didn’t talk about water when cleaned his cage. He would stick his head under the bottle, lift it up, drop it and wait. If nothing happened he would do it again and repeat the action until someone said the word “water.” Usually in the form of the sentence: “Okay, Archie, I’ll get you water, just wait a minute!”

In a few months there were many words that Archie knew and several he was fond of. “Water”, “treats”, “kisses” and “snuggles” were all favourites, but he also knew the meanings of “yes” and “no”, along with many other useful words. He could also tell the difference between a single “no”, which we used to emphasize new rules, and “no, no, no”, which we used to remind him of rules he already knew how to follow (like no rats on the floor). I began to work with this increasing vocabulary, certain that there would be a way to help him call to us like the fish did or to express his needs. I bought little jar lid attachments, intended to help the blind label things. You record a short message then push the button to play it back. I began teaching Archie to push the buttons and that pushing the buttons would give him the reward of the thing that he had “requested.” The hardest part was helping him understand that when he heard the word “kisses” come out of the device, it meant he would GET kisses, not that he should GIVE them. Sadly, just as he was learning this he became sick and then passed away, so I will never know how far this training could have gone with him.

Our latest boy, North, will be featured in another article about helping animals adjust to new routines because his communication is the strongest when something is supposed to happen and doesn’t. For instance, when the power goes out and we then can’t turn the lights on when it gets dark, he dashes around looking up at light bulbs and pulling on our arms. His communication is always very clear. In this case you can almost see the speech bubble over his head: “Stupid humans. It’s dark, make it light again!”

The point of all of this is that I have had many people tell me they wished they could have the same connection with animals that I do. Often they ask me what my secret is. How is it that even as a three year old child I seemed to be able to interact with animals in a way that they completely understood? How did I get them following me around or “listening” to what I was telling them to do? There is only one answer: observation. It’s something you need for any language. In order to learn how to say “teddy bear” in such a way that someone else understands it, you have to figure out what word the other person uses for “teddy bear.” The same is true when “talking” with animals; you just have to switch your mind into a different, physical, form of communication. Sometimes “I’m so glad you’re here!” really sounds like water slapping against the glass of a fish tank. Accepting that is the first step to really “talking” with the animals around us.

Mirrani Houpe, our Small Animal Editor, has had rats since she took home her first little boy once they both completed the second grade. Since that time she has owned, rescued and bred many kinds of rats, from many backgrounds. She may not be a vet, psychology major, or scientist, but her babies have her very well trained when it comes to how to care for them. She is constantly working with her family’s veterinarian to come up with new and innovative ways to love and care for the most often misunderstood rodent in the pet world. You can e-mail her at mirrani@yourpetspace.info